Cymraeg / English

|

Back Home |

|

|

|

Historic Churches Survey Database |

Caring For Church Archaeology

The following pages have been compiled from the booklet Caring for Church Archaeology, published in 2000 by Cadw: Welsh Historic Monuments and the Welsh Archaeological Trusts. This marked the end of a four year project to survey and record all pre-nineteenth century churches across Wales. As well as the booklet the survey produced detailed reports about each church which are included here in the Historic Churches Survey database section.

Church Archaeology

|

|

Because of this they provide a strong physical link with the past and have a fascinating story to tell about the history of the communities that built them and continue to maintain them. The care and maintenance of historic churches therefore needs to be carried out with respect to their historical and archaeological value as well as to their primary role as places of Christian worship.

To help our understanding of historic churches in Wales, Cadw: Welsh Historic Monuments sponsored the four Welsh archaeological trusts to undertake an archaeological survey of the historic churches in the six dioceses of the Church in Wales, covering around 1,000 churches that were either built before the beginning of the nineteenth century or which lie on sites established before that time.

The results of this fieldwork and research are included in a series of individual church reports and regional surveys which are available from the trusts.

This section draws upon the Wales-wide survey and looks at what archaeology can tell us about the history of Welsh churches, and how this rich archaeological heritage can be preserved and managed.

Church Archaeology

Archaeology provides important insights into the history of a church and the community it serves, helping to tell us when and why a particular church was founded, who founded it, how and by what stages it was built, what it was originally like inside and how its appearance has changed through time.

Left & below: Archaeological excavation at St Melangell's Church, Pennant Melangell, Powys, was carried out hand-in-hand with restoration work and helped to elucidate the early history of the church. The excavations revealed the footings of a twelfth-century apse built as a cell y bedd, or grave chapel, above the grave of the eighth-century female saint to whom the church is dedicated. The apse has been restored.© CPAT

Left & below: Archaeological excavation at St Melangell's Church, Pennant Melangell, Powys, was carried out hand-in-hand with restoration work and helped to elucidate the early history of the church. The excavations revealed the footings of a twelfth-century apse built as a cell y bedd, or grave chapel, above the grave of the eighth-century female saint to whom the church is dedicated. The apse has been restored.© CPAT

|

Archaeology also looks at how the churchyard has changed and the place of the church in the history of the town, village, or countryside in which it lies. Church archaeology is concerned with evidence to be found both above and below the ground and involves many different disciplines - the study of historical, genealogical, and place-name evidence; analysis and recording of walls, wall-plaster, floors, and roof-timbers; topography; art history; and the study of the many different kinds of fixtures and fittings including woodwork, wall paintings, stained glass, metalwork, gravestones, and other graveyard furniture. It makes use of a number of modern techniques - such as aerial photography or geophysical survey - to reveal traces of graves, buried walls, or vaults no longer visible at ground level. Where preservation is impractical, church archaeology may involve the study and interpretation of buried remains by excavation, involving work by specialists in human anatomical remains, medieval pottery, soils, geology, plant remains, and early technology.

A Unique Story

Each of our historic churches has a unique story to tell. Some were evidently founded by religious men or women in the early medieval period and dignified with the title of saint.

A number of the larger churches began life as native Welsh monasteries or clasau, often set within circular churchyards, whilst some of the smaller ones were first established as dependent chapels of a mother church, or as the private chapel of a local Welsh lord or noble. Some were first built when the new Anglo-Norman settlements were created in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, or in the new towns which sprang up across Wales following the Edwardian conquest in the later thirteenth century.

|

|

Several present-day parish churches once belonged to monasteries or abbeys that were closed down during the reign of Henry VIII (1509-47). Others were new foundations of the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. Even a small and apparently simple church, thoroughly rebuilt in the Victorian period, may none the less still preserve important evidence dating back to the beginnings of Christianity in the British Isles.

The Fabric Of The Church

Much still remains to be learnt about the plans of earlier Welsh medieval churches. Often, the only way of finding out about the history of the church building is by looking for changes in build in the standing walls, or by looking for traces of earlier timber buildings or earlier stone footings which survive below later walls and floors.

Left: Changes in the build can often tell us a great deal about the history of a church. At St Bilo's Church, Llanfilo, Powys, the present building appears to belong to the 13th or 14th centuries. However this former priest's door in the north wall has reused an apparently Norman carved stone as its lintel and this suggests an 11th or 12th century church once occupied the site. Post Medieval changes in the church layout have in turn lead to the blocking of the door which is now partly below the present interior floor level. © CPAT

Date-stones are uncommon before the seventeenth century and few written records of church building survive before the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Something is known about the form of a number of the major clas churches from the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries - a period when many new churches were built in Wales - but little is known about the structures which preceded them. Our knowledge of the lesser churches and chapels is even more scanty, though archaeological excavation is beginning to show that some early churches were of types which no longer survive in Wales today, including churches that were built of wood or churches with curving apses at both the eastern and western ends.

Church Interiors

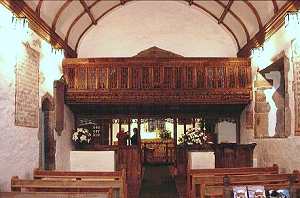

Right: The interior of the small and lonely church of St Issui at Patrisio, Powys, demonstrates the changes in religious practices over the centuries. In the nave,which is dominated by its finely carved rood screen and loft, there are earlier stone side altars and a later pulpit. Eighteenth century religious texts are painted on the walls. In most churches, earlier fittings were swept away during the Reformation and only archaeological recording and excavation can show how the internal layouts evolved over time.© CPAT.

Right: The interior of the small and lonely church of St Issui at Patrisio, Powys, demonstrates the changes in religious practices over the centuries. In the nave,which is dominated by its finely carved rood screen and loft, there are earlier stone side altars and a later pulpit. Eighteenth century religious texts are painted on the walls. In most churches, earlier fittings were swept away during the Reformation and only archaeological recording and excavation can show how the internal layouts evolved over time.© CPAT.

Church interiors have also altered considerably over the centuries, often in response to changes in the acts of worship. Many churches seem to have had simple earthen floors strewn with rushes until as late as the eighteenth century. It was a regular custom to bury the more prominent members of the community inside the church until this time, often in relatively shallow graves. Little or no seating was provided for the congregation until the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, following the growth of preaching during the later Tudor period. Where they survive, early floors can be helpful in showing how the interior of the church used to be laid out, including where, for example, fonts, altars, rood screens or shrines once stood. Early floors are also important to the archaeologist in helping to relate different periods of building activity in different parts of the church and occasionally by producing artefacts which help to date them. The inside walls of early churches were often elaborately decorated with colourful patterns or religious scenes. Many of these paintings were obscured by limewash during the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, sometimes being replaced by the Royal Coat of Arms or religious texts in Welsh or English. Traces of early painting of this kind can often be found below later layers of wall plaster.

Roofs And Ceilings

Roofs and ceilings provide a wealth of information about the master carpenters and their work and the styles that were adopted in different areas of Wales.

Expert attention from conservators is needed to ensure that paintings of this kind are preserved for the future.

© Hirst Conservation. Left: This part of the late fifteenth or early sixteenth-century wooden ceiling in the chapel of St Elian's Church, Llanelian-yn-Rhos, Conwy, is painted with a scene showing the Adoration of the Shepherds. The medieval Welsh poet, Sion Cent, was moved by the skill with which images of this kind were painted:

Left: This part of the late fifteenth or early sixteenth-century wooden ceiling in the chapel of St Elian's Church, Llanelian-yn-Rhos, Conwy, is painted with a scene showing the Adoration of the Shepherds. The medieval Welsh poet, Sion Cent, was moved by the skill with which images of this kind were painted:

Painting many images

And a host of saints with the colours of the stars."

The date when a medieval roof was erected is often a matter of guesswork, however, and if major repairs are being undertaken it may well be worthwhile commissioning a programme of tree-ring dating to find out very accurately when a roof was built. Rarely has any of the original roof covering survived, and the only evidence may be that found by archaeological excavation.

Furnishings And Fittings

Many of the treasures of the medieval church in Wales have, sadly, been lost. Precious objects were plundered during the Viking raids of the eleventh century, or were looted during the Welsh wars of independence in the late thirteenth century and the Glyn Dwr uprising at the beginning of the fifteenth century.

As in England, much was lost during the Reformation in the sixteenth century and during the course of the Puritan reforms of the seventeenth century, when many altars, shrines, and relics were stripped away.

Left: Prince Brochwel, figured on the fifteenth-century rood screen at Pennant Melangell, Powys. The carving forms part of a frieze which gives us the earliest representation of the legend of St Melangell, probably based on an oral tradition stretching back to at least the eighth century. It is appropriate that late medieval Welsh poets were fond of likening their literary skills to those of the wood carver. © CPAT

Left: Prince Brochwel, figured on the fifteenth-century rood screen at Pennant Melangell, Powys. The carving forms part of a frieze which gives us the earliest representation of the legend of St Melangell, probably based on an oral tradition stretching back to at least the eighth century. It is appropriate that late medieval Welsh poets were fond of likening their literary skills to those of the wood carver. © CPAT

|

As late as the eighteenth and early nineteenth century many richly ornamented late medieval rood screens were removed to make way for more seating. Early box-pews and other fittings were removed for similar reasons in the late nineteenth century. The items that have survived — early memorials, bells, musical instruments, altar furniture, silverware, stained glass, fabrics, paintings, rood screens, shrines, reliquaries, chests, fonts, candelabra, doors, or bell-frames — assume an even greater importance, and may require specialist conservation to ensure their continued survival.

Churchyards

Churchyards are equally significant for the information they preserve about the history of the church and its community. Memorial stones, tombs, churchyard crosses, sundials, or even a ring of yew trees, are all important to our understanding of the social and cultural history of the local community.

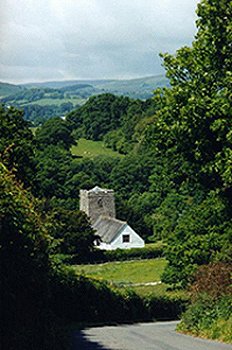

Right: Aerial view of St Michael's Church, Llanfihangel Helygen, Powys, shows the church set in a small circular churchyard defined by mature trees. Although the present church appears to be no older than the 17th century, the size and shape of the churchyard and the isolation of the site may well indicate that the church has an early medieval origin.

© CPAT

Right: Aerial view of St Michael's Church, Llanfihangel Helygen, Powys, shows the church set in a small circular churchyard defined by mature trees. Although the present church appears to be no older than the 17th century, the size and shape of the churchyard and the isolation of the site may well indicate that the church has an early medieval origin.

© CPAT

|

Ancillary buildings may also be of interest. The stables attached to some churchyards, for example, are a reminder of the way in which the Welsh rural clergy used to serve their dispersed parishes. Churchyards may also preserve evidence buried in the ground, perhaps showing that a site was first used in the pre-Christian era or that a churchyard was originally of an entirely different shape and size.

Churches In The Life Of The Community

Churches have always been important gathering points, particularly within early Welsh rural communities, and may provide evidence of the non-religious activities that took place in and around them, including sporting events or fairs at which goods were bought and sold. Little or no visible evidence has survived of the mystery plays known to have been performed in churches and churchyards during the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, but occasional traces are to be found of the ball games or other activities which used to take place. Even cockpits are known inside some churchyards. Many of these activities have their origin in the medieval gyl mabsant - the feast of the patron saint - many of whose traditions fell out of custom during the later eighteenth and earlier nineteenth centuries.

|

|

Managing The Archaeology Of Historic Churches

As well as fulfilling its primary role as a place of worship, an historic church can illuminate the history of a community and also provide a valuable resource for educational or tourism initiatives.

Right: The splendid early sixteenth-century tower of St Giles's Church is one of the few visible reminders of Wrexham's position as one of the larger Welsh medieval settlements. The church is first mentioned in the early thirteenth century but was probably founded at a much earlier date, possibly as part of an original Saxon settlement. Deposits buried below the church and modern town are now our only potential source of information about the earliest church and settlement. © CPAT

Some historical information can be gleaned from historical documents or from the building itself, but much of a church's history still awaits discovery, hidden in the ground or in the very fabric of the building. Archaeological remains are often fragile, and can be damaged or destroyed inadvertently. Alterations and repairs to historic churches should therefore be carried out sympathetically, in a way that enhances our understanding and appreciation of them, and minimizes the loss of irreplaceable archaeological information.

Ecclesiastical Exemption

Ownership of the majority of churches and their fittings in Wales is vested in the Representative Body of the Church in Wales, with individual parishes bearing the responsibility of looking after them. With the exception of very minor or emergency works, all other changes or repairs to churches, churchyards, fixtures and fittings, need the approval of the appropriate Diocesan Chancellor. Each chancellor is advised by a Diocesan Advisory Committee (DAC) which includes members with a knowledge of historic buildings and archaeology. Where appropriate, the DAC will seek advice from other special interest groups, such as the Victorian Society, the Georgian Society, the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, and the Council for British Archaeology. Because of these procedures, churches have ecclesiastical exemption from many of the listed building controls operated by the local planning authority.

Right: Many parishes have responsibility for safeguarding early crosses, ancient tombstones or architectural fragments. This fine cross slab housed in St Dogfan's Church, Llanrhaeadr-ym-Mochnant, Powys acts as a vivid reminder of the early monastery which once occupied the site. © CPAT

These are cases where listed building and conservation area controls continue to apply; for example, where work will affect other buildings or structures within church grounds which are also listed, where works are to be carried out other than on behalf of the church, or where total demolition is proposed. Planning permission will also be needed where, for example, proposals involve change of use, the construction of new buildings, changes to access or floodlighting, or the extension to a burial ground. If the works affect a scheduled ancient monument, such as an archaeological site or an inscribed stone inside a churchyard, scheduled monument consent will also be needed from Cadw: Welsh Historic Monuments. Local authorities and Cadw both normally seek the advice of other bodies when applications are submitted to them, and additional archaeological advice may be given as a result. It may also be necessary to bear in mind the legislation and regulations affecting the removal of skeletal remains from consecrated ground. Similar considerations may also apply to redundant historic churches.

|

Seek Advice EarlySeek advice if there is a chance that proposed works will affect archaeological remains, remembering that it is always best to get advice early on, while proposals are still being discussed, and well before any work is undertaken. Conservation work, recording or excavation may be expensive, and having a clearer idea of what is involved will enable the church architect, for example, to make allowance for archaeological recording in a schedule of works, and to make provision for the cost of this work in applications submitted to grant-awarding bodies. |

Who To Ask For Advice

- Each of the six dioceses of the Church in Wales has an archaeologist who advises the Diocesan Advisory Committee (DAC). They will provide advice on the archaeological implications of schemes of work affecting churches put to the DACs for consideration.

- Cadw: Welsh Historic Monuments is the government agency responsible for advising the National Assembly for Wales on the scheduling of ancient monuments and listing of historic buildings. As well as providing technical advice, grants are also available from Cadw towards the cost of practical conservation work and repair. Consent must be obtained from Cadw for works affecting scheduled ancient monuments.

- Local authorities have conservation officers who are able to offer advice on the preservation of listed buildings and broader conservation issues including those associated with conservation areas.

- The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales (RCAHMW) holds the National Monuments Record (NMR) for Wales, the central record of all archaeological and historical sites in Wales. Commission staff may be able to provide information on historic churches and to carry out emergency recording work on listed buildings.

- The four Welsh archaeological trusts maintain the regional Sites and Monuments Records (SMRs) — the comprehensive records of the cultural heritage for their areas — and provide wide-ranging archaeological advice through their curatorial services. The SMRs include reports on individual churches resulting from the archaeological survey of Welsh historic churches recently sponsored by Cadw, copies of which are available on request.

|

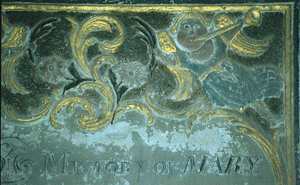

Left: Part of a painted wall tablet inside St Martin's Church, Cwmyoy, Monmouthshire. The carving is by John Brute (1752-1834), a member of the third generation of Brutes from Llanbedr whose work can be found in numerous churches in the area of the Black Mountains in Breconshire and Monmouthshire. Monuments of this kind are important examples of local craftsmanship and popular taste in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Wales.© Liz Pitman. |

Key Regulations, Legislation & Planning Guidance For Historic Churches In Wales

- The Constitution of the Church in Wales, The Canons and The Rules and Regulations, 1995. Rules and regulations affecting changes to churches, church grounds and fixtures and fittings inside churches in the possession of the Representative Body of the Church in Wales.

- Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. Legislation relevant to churches and other associated buildings and structures classed as listed buildings or falling within conservation areas.

- The Ecclesiastical Exemption: What it is and How it Works, Department of National Heritage and Cadw: Welsh Historic Monuments, 1994. Summary of procedures for ecclesiastical buildings or structures exempt from listed building controls, as operated by individual dioceses within the Church in Wales.

- Ancient Monuments & Archaeological Areas Act 1979. Legislation relating to archaeological sites and monuments of national importance, protected as Scheduled Ancient Monuments. This rarely affects churches themselves, but may be relevant to archaeological sites within churchyards, inscribed stones, churchyard crosses, or ruinous medieval buildings.

- Planning Guidance (Wales) Welsh Office 1996. Provides the general framework for Welsh Office Circulars 60/96 and 61/96 detailed below.

- Welsh Office Circular 60/96 Planning and the Historic Environment: Archaeology. Provides detailed advice and guidance on best practice. It explains criteria for scheduling and recommends procedures for assessment, evaluation, preservation and mitigation.

- Welsh Office Circular 61/96 Planning and the Historic Environment: Historic Buildings and Conservation Areas. Sets out advice on legislation and procedures relating to historic buildings and conservation areas and guidance on best practice.

- Historic Buildings Grants & Conservation Area Grants, Cadw: Welsh Historic Monuments 1997. Outlines what grants Cadw can give for historic buildings and conservation areas, and it explains how you can find out more about these grants.

- Development Plans for each local authority area and national park contain policies designed to protect archaeological sites, historic buildings, and historic landscapes.

|

"Tried the echo in the field against the belfry and the west end of the poor humble dear little white-washed church sequestered among its large ancient yews. The echo was very clear, sharp and perfect. Richard Meredith told me of this echo."

|

Suggestions For Further Reading

Stephen Friar, A Companion to the English Parish Church (Stroud 1996).Warwick Rodwell, Church Archaeology (London 1989).

John Blair and Carol Pyrah (editors), Church Archaeology: Research Directions for the Future (York 1996).

J H Bettey, Church and Parish: A Guide for Local Historians (London 1987).

Inside Churches: A Guide to Church Furnishings (National Association of Decorative and Fine Arts Societies 1993).

Privacy and cookies

Right: St Mary's Church, Meifod, Powys, is set in an unusually large circular churchyard and during the early medieval period was one of the most important monastic sites, or Clasau, in Wales. The present church, although largely Victorian, contains elements of a 12th century church, which is one of the three churches which co-existed within the enclosure from this time. Traditionally the site is associated with the Princes of Powys who held court at Mathrafal, some 3km away, and the elaborate 12th century grave slab preserved in the nave of the church may originally have marked one of their burial's. © CPAT.

Right: St Mary's Church, Meifod, Powys, is set in an unusually large circular churchyard and during the early medieval period was one of the most important monastic sites, or Clasau, in Wales. The present church, although largely Victorian, contains elements of a 12th century church, which is one of the three churches which co-existed within the enclosure from this time. Traditionally the site is associated with the Princes of Powys who held court at Mathrafal, some 3km away, and the elaborate 12th century grave slab preserved in the nave of the church may originally have marked one of their burial's. © CPAT.

Left: St Mary's Church, Ruabon, Wrexham, in its circular churchyard, is still at the hub of the settlement. Other churches were built in isolated locations or have lost their associated settlements. Archaeological investigation can often establish why a church was built in a particular place. © CPAT.

Left: St Mary's Church, Ruabon, Wrexham, in its circular churchyard, is still at the hub of the settlement. Other churches were built in isolated locations or have lost their associated settlements. Archaeological investigation can often establish why a church was built in a particular place. © CPAT.

Right: The Reverend Francis Kilvert, the nineteenth century diarist, visited Colva church in Powys on 26th February 1870, he wrote:

Right: The Reverend Francis Kilvert, the nineteenth century diarist, visited Colva church in Powys on 26th February 1870, he wrote: